News - Asia and Pacific

GLOBE Goes to Sea

If you open a map of GLOBE Clouds data, you’ll see observations dotting the world’s oceans. The location is no mistake: Volunteers and students have been bringing GLOBE to sea.

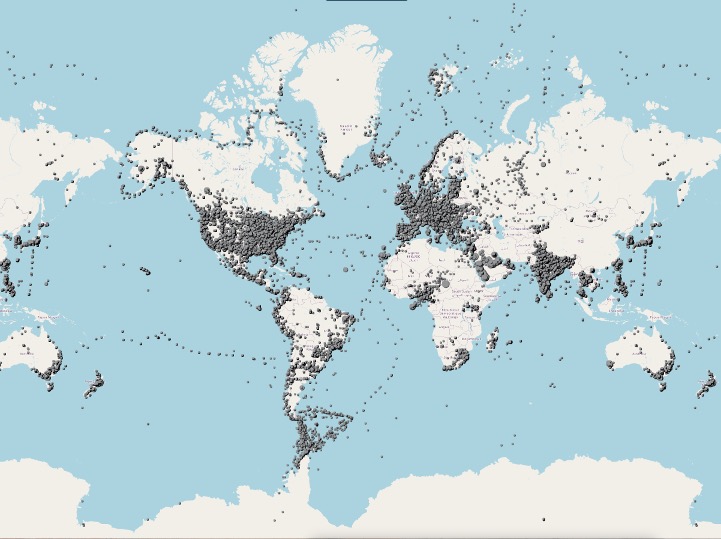

This map shows GLOBE Clouds observations collected between June 2019 and June 2024. Tracks across the oceans reveal that volunteers are taking GLOBE to sea.

This map shows GLOBE Clouds observations collected between June 2019 and June 2024. Tracks across the oceans reveal that volunteers are taking GLOBE to sea.

Take, for example, students featured in GLOBE Stars in June 2024. GLOBE alumna Ashlee Wells and a group of fellow GLOBE students recently completed a tall ship voyage from Japan to Palau as part of the Japan-Palau Friendship Yacht Race. In addition to learning to sail the three-masted schooner, the students made atmospheric observations (cloud, wind speed, direction, barometric pressure, relative humidity, and temperature) and ocean observations (temperature, pH, salinity, dissolved oxygen, nitrates, and phosphates).

Students sail the tall ship MIRAIE into the waters of Palau as part of a 16-day journey that included collecting GLOBE data. Photo credit Christi Buffington.

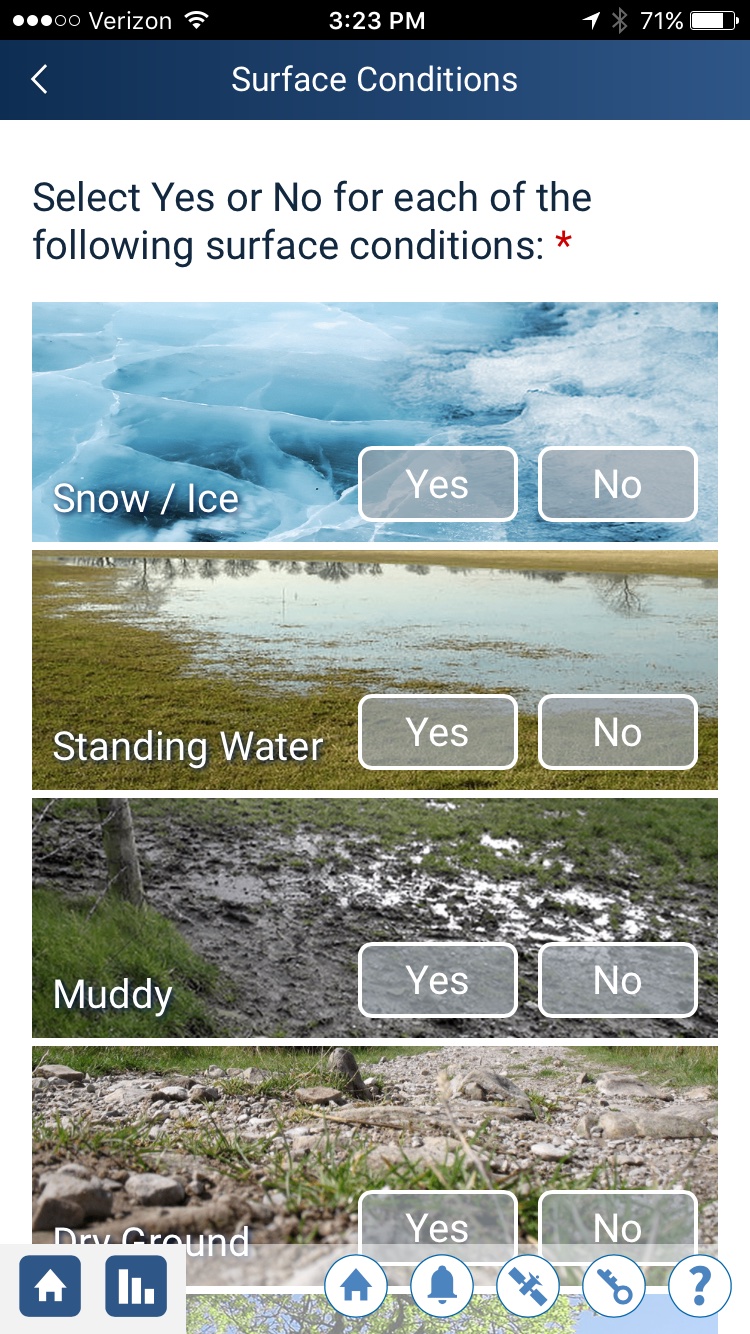

Their track is not the only ocean voyage visible in GLOBE data. GLOBE Clouds is a stapl e on many cruise ships, particularly polar expeditions. “Many operators hire Education Coordinators and Citizen Science Coordinators, and they look for interesting projects that can be done on ships,” says Allison Cusick, who has served as an education coordinator on such ships. “We give the traveling guests an introduction to the citizen science on board, including what it is, why it is important, and why data is limited in Antarctica. The first project we usually do is GLOBE Clouds because on sea days we need to fill the days with on ship activities as we do not stop the ship to get out for any excursions until we hit Antarctica.” After being trained, guests use GLOBE Observer to take clouds observations. “Everyone always laughs at the questions ‘Is there mud? Are there trees? Is there standing water,’ since we are in the Southern Ocean!”

e on many cruise ships, particularly polar expeditions. “Many operators hire Education Coordinators and Citizen Science Coordinators, and they look for interesting projects that can be done on ships,” says Allison Cusick, who has served as an education coordinator on such ships. “We give the traveling guests an introduction to the citizen science on board, including what it is, why it is important, and why data is limited in Antarctica. The first project we usually do is GLOBE Clouds because on sea days we need to fill the days with on ship activities as we do not stop the ship to get out for any excursions until we hit Antarctica.” After being trained, guests use GLOBE Observer to take clouds observations. “Everyone always laughs at the questions ‘Is there mud? Are there trees? Is there standing water,’ since we are in the Southern Ocean!”

The observations do more than fill time while travelers are at sea: “They offer a unique perspective that would otherwise be very difficult to obtain. The ocean covers 70 percent of Earth’s surface,” notes Maria Vernet, a marine phytoplankton ecologist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego. Ground-based observations of clouds over the ocean can only happen on ships, and since both clouds and the ocean are significant parts of the global water cycle, such observations are valuable. “The interaction between ocean and atmosphere sets up global climate and weather patterns,” says Vernet. “Clouds are how ocean water is transported to the land as fresh water.”

Oceans and clouds are both significant components of the water cycle, which is one reason why GLOBE clouds observations at sea, such as this one, are valuable. Credit: The GLOBE Program

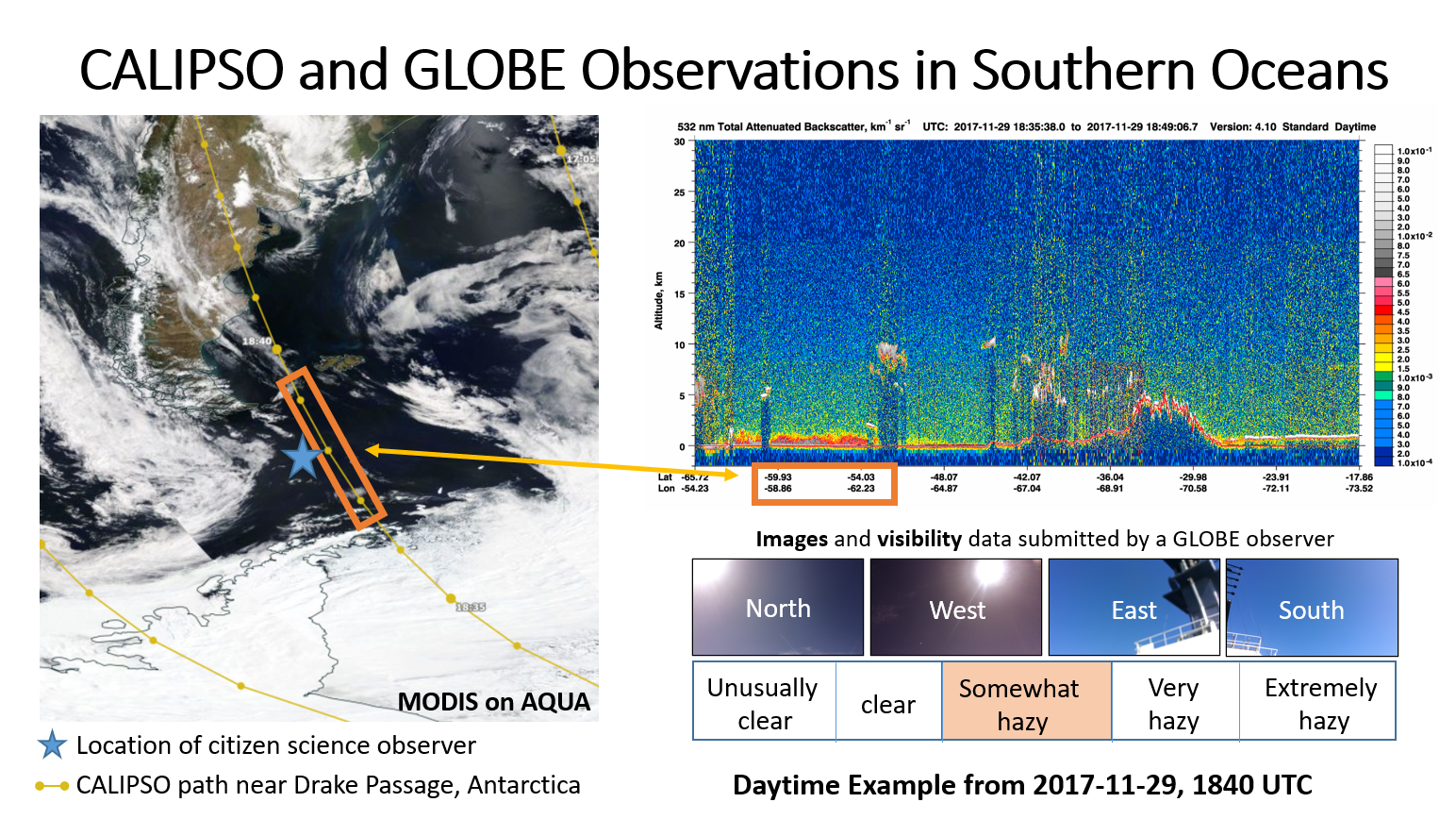

The observations provide complementary data to support the study of ocean clouds using satellite data. One of the initial analyses of data coming from polar expeditions was of clouds in the Drake Passage between South America and Antarctica, says GLOBE Clouds science lead, Marilé Colón Robles. CALIPSO satellite data, which used LiDAR to map a narrow three-dimensional slice of the clouds, often detected what might have been a thick layer of low clouds near the ocean’s surface, but it wasn’t clear what was actually happening. Looking at volunteer observations from 2018, “we could see haze coming from South America on what was otherwise a clear day. That was probably what CALIPSO was seeing,” says Colón Robles. “Volunteers have the best view of what clouds are over the ocean near the poles.”

The MODIS satellite view (left) showed clear skies over the Drake Passage on 29 November 2017, when CALIPSO captured the data shown in the upper right. However, the strong red line just above the ocean indicates that CALIPSO was recording some kind of cloud near the surface. Which was correct, MODIS or CALIPSO? GLOBE volunteers on a ship confirmed hazy skies, with haze coming from South America – the low cloud CALIPSO detected. Images from Marilé Colón Robles.

Today, Colón Robles is watching volunteer data from Antarctica for lenticular clouds, a unique stratus cloud formed by the interaction between land and atmosphere. The interaction between land, ocean, and atmosphere in Antarctica is unique. Studying cloud patterns there has provided unique insight into how atmospheric dynamics resulted in an ozone hole.

Further study of cloud patterns in polar regions may yield other important insights. “The cloudiest regions on Earth are the poles,” says Colón Robles. What’s more, the poles are more difficult to study using satellite data. In every other part of Earth, geostationary satellites (weather satellites) provide a constant view of clouds, but no such satellites cover the polar regions. Satellite data of polar clouds comes from polar orbiting satellites, which return a single view of the pole on every orbit around the planet. Ground-based citizen science can help fill in the gaps.

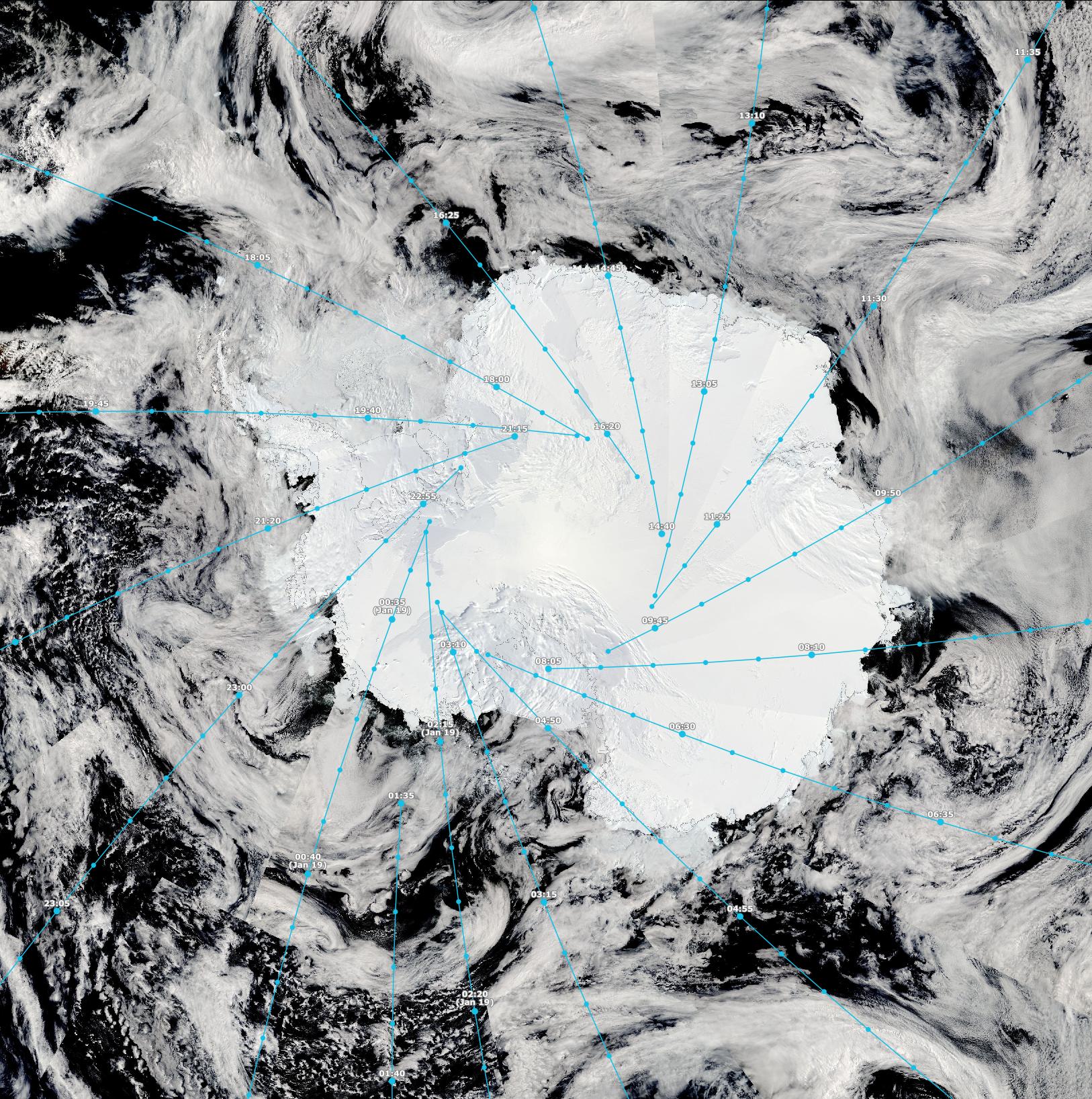

This view of Antarctica is a composite of multiple passes from the MODIS instrument on NASA’s Aqua satellite on 18 January 2024. A close look reveals wedge-shaped patterns and discontinuities in the cloud patterns. The blue lines indicate the center of each overpass used in the image. The image took a full day to compile. If a geostationary satellite were in orbit to view Antartica, it would get a similar view every few minutes. Image credit: NASA Worldview

This view of Antarctica is a composite of multiple passes from the MODIS instrument on NASA’s Aqua satellite on 18 January 2024. A close look reveals wedge-shaped patterns and discontinuities in the cloud patterns. The blue lines indicate the center of each overpass used in the image. The image took a full day to compile. If a geostationary satellite were in orbit to view Antartica, it would get a similar view every few minutes. Image credit: NASA Worldview

The collaboration between Antarctic tour operators, polar guides, travelers and GLOBE scientists stems from the Polar Citizen Science Collective, formed by polar guides Lauren Farmer, Annette Bombosch, Bob Gilmore and others to encourage expedition vessels to engage in science. They started using GLOBE Clouds in the 2016-2017 season, just after the GLOBE Observer app launched.

GLOBE Observer may soon have an expanded role in studying oceans in polar regions. Vernet plans to experiment using GLOBE Trees to estimate the height of icebergs in Arctic waters. Melting icebergs are one of the ways freshwater enters the ocean in polar waters. Vernet wants to know how fresh water affects coastal phytoplankton populations. If meltwater increases in a warming climate, what does that do to phytoplankton? The answer is critical because phytoplankton are the base of the marine food chain, and coastal waters, where icebergs are most abundant, are particularly critical for marine life of all varieties.

Expedition guests photograph an iceberg in polar waters. Photo courtesy Allison Cusick.

“We want to try to measure the abundance and type of icebergs with GLOBE,” says Vernet. Satellites provide a view of the ice extent and the extent of phytoplankton. “What GLOBE gives us is a 3D view of the ice. You do that already with trees.”

If successful, the GLOBE iceberg measurements would complement volunteer measurements of phytoplankton collected through Fjord Phyto. Vernet started working with tour expeditions in 2015 when on a research trip to Antarctica. She had set up a moored buoy with instrumentation to measure phytoplankton abundance off the coast of Antarctica year-round. However, when she returned to the buoy, it had become unmoored and drifted far away, its instruments battered by drifting ice. Retrieving the ruined equipment, Vernet recalls noticing a tour ship in the distance. She realized that they were frequently in the very waters she wanted to monitor, not year-round, but more frequently that she herself could sample. She approached polar guide Bob Gilmore and asked him if they could collect water samples during every trip. That partnership has expanded and grown into the NASA-funded Fjord Phyto project, cofounded by Vernet, Reynolds and Cusick.

A sample of GLOBE Cloud photos taken by volunteers on ships (top row and lower right photos) and guests collecting data (left and bottom center). Credit: The GLOBE Program (observation photos) and Allison Cusick (guests on ships).

Gilmore now engages travelers to collect FjordPhyto phytoplankton data, GLOBE Clouds data, and other citizen science data on multiple ships in the Antarctic every year. “Ground-truthing satellites is kind of cool,” he says. “On top of that, you give good feedback [with the satellite match emails],” something that participants on his ships appreciate.

In turn, GLOBE and scientists like Colón Robles appreciate volunteers and their observations, whether submitted from the backyard or the ends of the Earth.