I’m going to interrupt blogging about surprising liquid puddles and soil temperature to talk about the Second Pole-to-Pole Videoconference, which took place yesterday (8 April 2008). Several scientists participated, as did five schools: in Ushuaia, Argentina, the Escuela Provincial No. 38 Julio Argentina Roca; and in Alaska, the Randy Smith Middle School (Fairbanks), Moosewood Farm Home School (Fairbanks), Wasilla High School (Wasilla), and Innoko River School (Shageluk). The Web Conference was hosted by the GLOBE Seasons and Biomes Earth System Science team, at the University of Alaska at Fairbanks.

Figure 1. Locations of the schools in Alaska. Courtesy Dr. Elena Sparrow

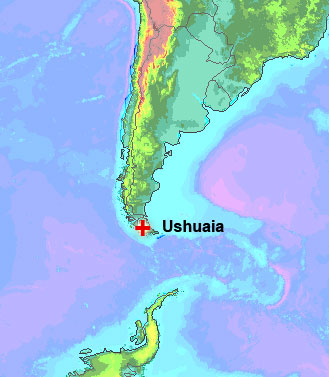

Flgure 2. Location of Ushuaia, which is near the southern tip of South America. Part of Antarctica appears on the southern part of the map.

The focus was on climate change, in particular:

- The most important seasonal indicators (things that change with season)

- Whether they are being impacted by climate change (if so, how?)

- How students could study these indicators to see if they are impacted by climate change.

As was the case last year, the students had an opportunity to ask questions of the students at the other schools as well as the scientists, but the conversation was more structured. We organized the conversations into three rounds. In Round 1, the Alaskan and Argentinean students were to ask each other about signs of seasonal change or share their own observations. In Round 2, the focus was on how to narrow questions down enough so that students could investigate them. And in Round 3, we were supposed to discuss the ways the investigations could be done.

The questions in Round 1 were wide-ranging. Why do leaves change color? Why is the soil frozen when the air is warm? Does the melting of permafrost cause damage to buildings and trees? Are glaciers disappearing? Do scientists use Native knowledge in their research? How does climate change affect plants and animals?

We learned that soil below ground warms and cools with the seasons more slowly than the air, and – the farther you go down, the less the temperature changes (this is also discussed in the previous few blogs). We also learned that the changes in the lower layers of the soil took place after the changes higher up (in scientific terms, the changes in the lower layers lags the changes in the upper layers). So a student was able to guess that late summer is the best time to test for permafrost, rather than the height of summer, when the sun angle is the highest.

We discovered that scientists are using Native knowledge in their research in many parts of the world, including not only Alaska and Canada, but also in Australia. We learned that magpies are coming farther north to Shageluk, and there are more pine grosbeaks than there used to be, although a student in Fairbanks didn’t notice any changes. We also learned that tree line is moving up in the mountains near Ushuaia.

In Round 2, questions focused on some fascinating things to investigate, including changes in the snowboarding season (of interest to students in both hemispheres), changes in temperature and precipitation, and succession of species after wildland fires. In fact, the students at Shageluk are already investigating the succession of species of some land recovering from a forest fire (see pictures at the Shageluk web site). The discussion of temperatures taught us the difference between maritime (Ushuaia and Wasilla) and continental (Fairbanks and Shageluk) climates: Ushuaia rarely gets below freezing, but Fairbanks has temperatures as low as -40 (same in Fahrenheit and Celsius), although such cold temperatures aren’t as common and persistent as they used to be). The discussion of snowboarding led to suggestions of investigating how long ski areas remain open, interviewing someone at a ski area about what conditions are good for snowboarding, thinking about what makes snow last (amount of precipitation, timing of precipitation, temperature). Two intriguing observations were that there were both more cumulus clouds in Ushuaia than there used to be, and more heavy rains.

With so many ideas generated in Round 2, some investigations were already outlined in some detail by the time we got to Round 3 – especially related to snowboarding. But snowboarding ideas continued to come up. A ski area had closed in Ushuaia, because its elevation was too low in the warming climate; and students in both hemispheres thought snowboarding might be an interesting thing to investigate together. Since the seasons are opposite, the study could be continuous.

Some new ideas also emerged about items to investigate. How about looking at when people take off or put on snow tires? Is that a good indicator of climate change? What about using frost tubes to monitor freezing and thawing in the soil in Ushuaia as well as Alaska? And how would frost-tube measurements relate to air temperature or the times that lakes and rivers freeze? And one could investigate the long-term seasonal geographic changes in diseases (mosquito-borne diseases, corn diseases).

It was pointed out to us that using a simple variable like temperature could yield some fascinating results beyond averages and simple trends. Is there a trend in how many days that the temperature stays above freezing? How about for the number of days when temperatures stay below freezing? How does this relate to precipitation? Clouds?

Also, we were reminded that not all changes we see are due to climate change – we humans are changing our environments in many other ways, such as destroying wilderness areas. And that trends we see in a few years can be quite different from the long-term trend. (That is, one cold winter doesn’t mean that it is getting colder on the long term.)

Through this rich mix of ideas for research topics and data to look at, the students continuously asked about each others’ lives. One of the most fascinating exchanges took place toward the end of the videoconference, when a student from Alaska asked the students in Ushuaia what kind animals they had and what kind of wildlife they ate. The Ushuaia students listed foxes, llamas, beaver, rabbit, birds, and penguins as the animals they had; and said that they ate rabbits, fish, and some beavers (but mostly tourists ate beavers). The beavers were apparently introduced to the region in 1946, and there are no natural enemies, so people are being encouraged to eat them.

A student from Shugaluk closed the discussion section of the conference by putting things in perspective. Yes, skate boarding and dog mushing are interesting, but for the Native peoples of the far North, their very way of life is being threatened. Earlier, a student in Ushuaia said that a glacier that was supplying water to the city was melting and would be gone in a few decades, leading to a shortage of drinking water. As one of the scientists said earlier, like the canary in the coal mine that warned of dangerous gases in a mine– the people in the Polar regions are the first to see the real danger in climate change. We need to remember this as we begin to take steps to try to slow down climate change and its impacts.

NOTES IN CLOSING:

There will be a web chat and web forum April 10-11. The purpose is to help students develop research ideas and projects, and interact with scientists. Links to the chat and forum can be found on the Pole-to-Pole Videoconference page of GLOBE Web site.

Three PowerPoint presentations describe the science and people of Ushuaia. They are also available on the Videoconference page at the above link.

Finally, I recall promising a student from Fairbanks that we would return to the topic of leaves changing color. Since we didn’t follow up on this question, I thought I would include a discussion here. The leaves change color because the chlorophyll, which gives the leaves their green color, disappears in the fall, so that other chemicals in the leaves give them their color. The chlorophyll, of course, is involved in photosynthesis, which provides plants the energy to grow. Different types of trees change different colors. For example, some maple trees turn bright red, while aspen trees turn yellow in the autumn. The weather actually affects how bright the colors are in the fall. In long term, the climate also affects the trees that can stay healthy in a given place. Thus the mix of trees, and hence the colors could change over many decades.

More information is available about leaf color under the Seasons and Phenology Learning Activities, Activity P5 “Investigating Leaf Pigments” in the Earth as a System Chapter of the GLOBE Teachers’ Guide.

The seasons and Biomes project is an effort to engage students in Earth system science studies as a way of learning science. It is a timely project for this fourth International Polar Year with many and intense collaborative research efforts on the physical, biological, and social components and their interactions. Changes in the Polar Regions affect the rest of the world and vice versa, since we are all connected in the earth system. I encourage students to conduct their own inquiry whether collectively as a class or in small groups, or individually. Students can use the many already-established GLOBE measurements in the areas of atmosphere/weather. soils/land cover/biology, hydrology, and plant phenology in their local areas (You can access the protocols by clicking on “For Teachers” on the menu bar at the top of the GLOBE homepage.) Soon there will be new measurement protocols such as fresh-water ice freeze-up and break-up protocols and a frost-tube protocol that will be posted on the GLOBE web site. Students can conduct a study on things that interest them as part of the upcoming GLOBE Student Research campaign.