This week we have a guest post from Janis Steele, PhD and Brooks McCutchen, PhD. They own and operate Berkshire Sweet Gold Maple and Marine, an agroforestry and ocean-going enterprise concerned with sustainable livelihoods and the preservation of wild and perennial ecosystems, from ridge-to-reef. Along with their three boys, Connor, Rowan and Gavin, they spend half of each year running their farm in the Berkshires in Western Massachusetts and the other half at sea aboard their sailing ketch, Research Vessel Llyr. In both settings–ridge and reef– they work on and study ways to promote and help build practices that support biological and cultural diversity, or biocultural diversity.

Early sailors traveling the world’s oceans were all too familiar with an area of the tropical seas characterized by lack of winds and violent thunderstorms. They called this zone “the doldrums” and dreaded being “stuck in the doldrums.” In his Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner, English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge offered the following description of the Pacific doldrums:

All in a hot and copper sky,

The bloody Sun, at noon,

Right up above the mast did stand,

No bigger than the Moon.Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, no breath no motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

Today, we have a better understanding of this phenomenon and now know this area as the Intertropical Convergence Zone, or ITCZ. It shapes atmospheric circulation patterns throughout the world and is considered to be the most prominent rainfall feature on the planet; critical in determining who gets fresh water and who doesn’t in the world’s equatorial regions. The ITCZ is defined by the coming together, or convergence, of the northern and southern hemisphere trade winds and a decrease in the pressure gradient. Specifically, in the north, trade winds move in a southwesterward direction originating from the northeast, with somewhat of the opposite effect in the southern hemisphere (where trade winds blow from the southeast to the northwest).

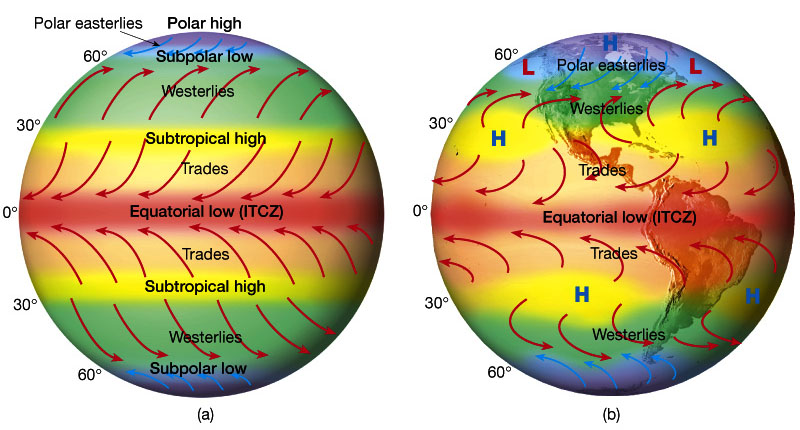

A) Idealized winds generated by pressure gradient and Coriolis Force. B) Actual wind patterns owing to land mass distribution.

From: Figure 7.7 in The Atmosphere, 8th edition, Lutgens and Tarbuck, 8th edition, 2001.

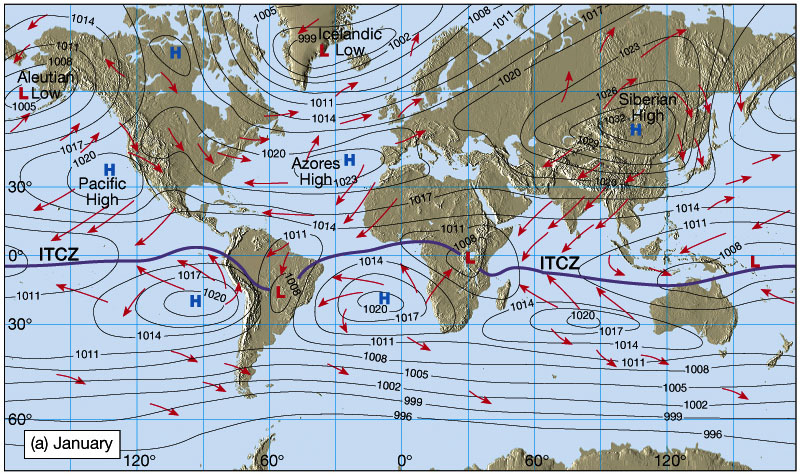

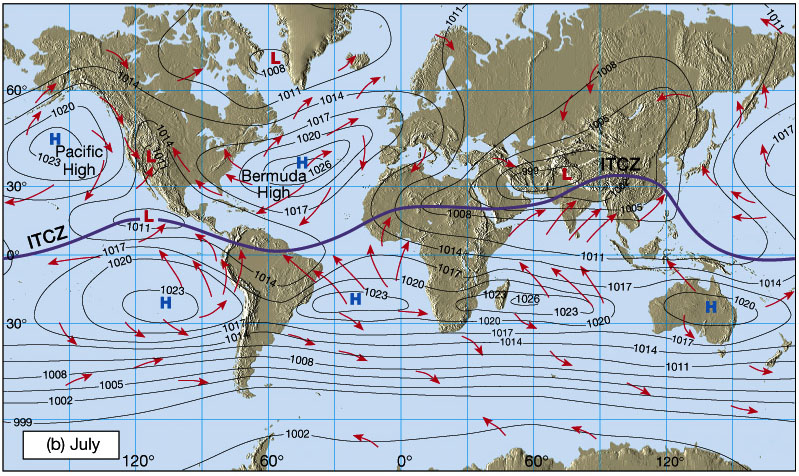

The intense tropical sun pours heat into the atmosphere forcing the air to rise through convection and results in precipitation. Rain clouds up to 9,144 m (30,000 ft) thick can produce up to 4 m (or 13ft) of rain per year in some places. The ITCZ is not a stationary phenomenon nor are its movements symmetrical above and below the equator. Many factors, including seasons and land masses, influence its overall movement.

Southern shift of ITCZ in January.

From Figure 7.9 in The Atmosphere, 8th edition, Lutgens and Tarbuck, 8th edition, 2001.

Northern shift of ITCZ in July.

From Figure 7.9 in The Atmosphere, 8th edition, Lutgens and Tarbuck, 8th edition, 2001.

With this knowledge in mind, we first encountered some of the effects of the ITCZ last year, as we approached the Caribbean coast of Panama aboard our sailing research vessel (RV) Llyr in July 2012. The map above shows the ITCZ located very near to Panama, the narrow strip of land that connects North, Central and South America. At a latitude of about 9°North, we met up with the storms of the ITCZ during the night. We could see the arrival of a band of storms on our ship’s radar and plotted a course to avoid them. The storms had other plans, and we spent the night in their midst, at times feeling like they were chasing us as we tried to take evasive action while they kept building right overhead. Lightning lit the sea around us in an eerie glow and we could see, through the rain, bolts striking not far from the ship. The next morning, tired but safe, we sailed into the harbor in Bocas del Toro, Panama, having had our introduction to the ITCZ.

We came to Panama as part of a multi-year research expedition aboard RV Llyr, studying coral reefs, sustainable fisheries and changes taking place in the ocean. As farmers, we have studied weather for many years, understanding oceans and atmospheric circulation as integrated systems that help produce weather at our forest farm in New England. As social scientists and human ecologists, our interest lies in researching the myriad links between biological and cultural diversity as key elements in sustainable development. In the coming weeks, we will transit the famous Panama Canal aboard our 53′ steel ketch, and once again pass through “the doldrums” as we make passage for the Marquesas in French Polynesia. During the 30+ day passage, we’ll be participating in global plankton studies and weather surveys. During our passages through the Pacific Islands, specifically French Polynesia, the Cook Islands, Tonga, and finally Fiji, we’ll perform reef surveys on scuba and hopefully meet with local schools to share the findings and experiences of our expedition. We are a family of five, with three boys on board, and additional crew members and scientists joining us on expedition. We look forward to sharing our journey.

Suggested activity: Do you live in a region affected by the ITCZ? We’d love to hear about your experience as these storms pass through. Send us a story or an image you have captured about the ITCZ either through a comment here, our website, or our Facebook page. Be sure to collect temperature and precipitation data to document how your location is affected by the ITCZ, and think about what influence these two atmospheric variables may have on other GLOBE protocols.

Absolutely wonderful and fascinating information about the Intertropical Convergence Zone.

Very interesting article about ITCZ. Early sailors named this belt of calm the doldrums because of the inactivity and stagnation they found themselves in after days of no wind. Thanks for sharing Jessica.

Very interesting article about ITCZ. Early sailors named this belt of calm the doldrums because of the inactivity and stagnation they found themselves in after days of no wind. Thanks for sharing Jessica.

i will help