This is my last blog as GLOBE Chief Scientist. I have greatly enjoyed sharing my thoughts with you. I have enjoyed hearing from many of you, not only through comments on the blog, but through emails, phone calls, and encounters at meetings. This blog enabled Kevin Czajkowski to keep in touch with teachers and students during the two surface temperature web-based field campaigns held in December of 2007 and 2008, with a quick-follow through showing students and teachers how the data were used. This, I hope, will be a model for GLOBE web-based field campaigns in the future. The blog was used by SCUBAnauts to share their experiences. The blog was used by GLOBE teachers in the classroom. My favorite blogs were those that I could use to share data with you, in hopes that you could work with the data – and perhaps collect some data on your own.

Science is – more than anything – about asking questions about Nature. And it’s a lot more fun to discover the answers from your own data, than to read about them in a book. It doesn’t matter that someone else found the answer earlier. It’s important for you to find out how to discover nature’s secrets on your own.

I already knew about the relationship between crickets and temperature. But it was tremendously satisfying to re-discover that for myself. (Do you remember the cricket blog?)

One message that I hope you have heard is that you can do some simple science investigations without many tools. You can do some simple investigations without buying expensive equipment. The cricket measurements can be made with a clock and a thermometer. You can take snow measurements with a ruler. Does the snow cover vary from one place to another? With time? You can test to see if the auditorium heats up when you fill it up for parents’ night or a special performance or speech. The instruments needn’t be expensive. Even an uncalibrated thermometer can tell you whether it gets warmer in the auditorium, for example.

Another message that I would like to leave with you is not to be afraid to ask questions. Your textbook might not be right. When I was just starting out as a researcher, my professor told me to take a textbook, open it up, and point to a random page. He said that something on the page was probably wrong in some way, and it was my job to find out. That’s the way science is. We keep learning. A fundamental part of that learning is carefully observing nature.

I feel extremely lucky to have seen the science related to greenhouse-gas warming of the Earth develop from a simple idea I first heard in the 1970s to an idea that is largely accepted by the scientific community today. I also feel lucky to have seen geologists accept continental drift. The process of scientific progress, as you may have seen from arguments in the media, is not always pleasant. It can even be painful. People have passionate opinions on both sides. I just received a long and somewhat desperate paper from a long-time friend and colleague who still doesn’t accept that human-generated greenhouse gases are responsible for the warming of the planet. But there is considerable evidence from observations and models that he is wrong.

Others who know less about science or who don’t want to accept the warming of the planet by us write things on the Web that can be easily exposed as false. Thus I have from time to time written about “misconceptions” about climate change. When you read about the changing climate – or any other aspect of nature – on the Web or in newspapers or magazines, remember your basic science. And remember to ask questions.

I have probably been less successful in writing about other countries. Writers are told to write about what they know – and I know the weather and climate of the United States the best, since I live here. I can observe the temperatures and puddles and snow and fires in Boulder, Colorado, because I live here. Perhaps in future blogs we can have guest bloggers from other countries to share observations and ideas.

What will be my future?

After I leave GLOBE, I will be a full-time scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. I will be doing research on how to represent the warming and moistening of the atmosphere by the surface and its vegetation in computer models used to predict the weather and climate. The plot in Figure 1 shows something I am interested in: how daytime surface temperature (related to how much the air near the surface is heated) and green plant density. Figure 2 shows where the data were collected.

Figure 1. Plot of the Normalized Differential Vegetation Index (NDVI), which describes the amount of green plants in a given area, against surface temperature measured by a Heiman radiometer. On the Eastern Track, which is in southeast Kansas, areas with lots of green (in this case grass) tend to be cooler, something we know from walking barefoot. On the western track (in the Oklahoma Panhandle), the surface temperature depends more on how wet the ground is than on vegetation, which is sparse. (For more about surface temperature, see the GLOBE Teachers’ Guide) The data were collected from the University of Wyoming King Air, flying along tracks shown in Figure 2, on 29 May 2002 (Western Track), 30 May 2002 (Eastern Track) and 31 May 2002 (Central Track). IHOP = International H2O Project.

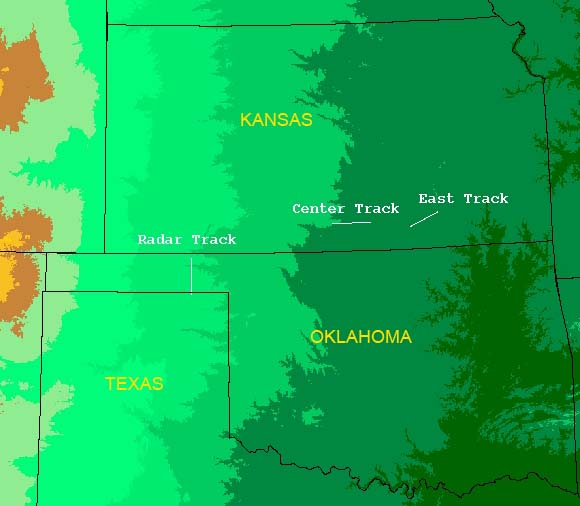

Figure 2. Map showing the locations of the flight tracks in Figure 1. The “Radar Track” in this Figure is the “Western Track” in Figure 1. The low NDVI in Figure 1 tells us there is little green vegetation along the radar (western) track. This is consistent with less rain there.

After a short break, I will continue to contribute (though less frequently) to a blog at another site here at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR, to be announced later). I hope you will continue reading the GLOBE blog, which will be undergoing some exciting changes. These will be announced in the next blog by Dr. Ed Geary, the GLOBE Director.

I will be retiring on 25 December 2009. But I will still be working – more for the joy of it rather than for pay. Younger people can use the salary more than I can. I am looking forward to serving as President of the American Meteorological Society, which has 14,000 members around the world, but mostly in the United States and Canada (I am currently President-Elect). I also will be continuing in my weather and climate research, but will also take more time for my other passions – paleontology (Figure 3), birding (Figure 4), and clouds (Figure 5), as well as my family and friends.

Figure 3. Segments of a Baculite. This fossil is a type of Ammonite that is straight rather than coiled. It is related to the modern Chambered Nautilus or Squid. From the Upper Cretaceous, Wyoming.

Figure 4. Wild Turkey, photographed on road from Roswell, NM, USA, to Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge.

Figure 5. Cumulus clouds over the foothills west of Boulder, Colorado.

Please remember the joy that comes with observing your world. But look carefully. And remember that nature is full of surprises.

Peace