By Dr. Charles Kironji Gatebe, NASA Scientist for GLOBE Student Research Campaign on Climate

We begin our journey up Mount Kenya at Met Station (shown in Figure 3, altitude 3050 m AMSL) early in the morning around 6 a.m., while the dew is still resting on the grass. The sun has not yet risen, but there is enough light to see our way through the bushes and to keep us safe from wild animals such as elephants, buffaloes, and leopards which dwell in this area, which is a protected national park. The animals usually retreat deeper into the forest during daytime, and like to stay away from the walking trails. However, we need to stay alert and beware of the wild animals wandering around in search of food, as they can be a danger to life. As we head out, the birds are already singing. We watch for silver Mountain Greenbul, Stulmans Sterling, various species of flycatchers — about eight in this area, Verreaux Eagles and many more.

Fig. 3: The Met Station on the southwestern slopes of the mountain. Most mountaineers prefer to spend a night here to help acclimatize to thinner air at 3050 m above mean sea level. The house in the background is used Kenya National Park Rangers, who help coordinate rescue operations. To the left of the house is a small meteorological station. Try to identify a rain gauge, a Stevenson’s screen and a wind vane in the picture. Note also the red volcanic soils. I took this picture in 1997 during a research expedition.

Our trail takes us through the forested zone and leads to an almost treeless zone (the moorland), which is dominated by swampy wet soils with amazing plants (many varieties of lobelias, tussocks, red hot pokers and giant senecio trees) and a varied topography. It is extremely difficult to walk in this zone, especially during a rainy season because of slippery ground. As we enter the moorland zone, we discover that we are above the treeline (>3300 m). From the Met Station to this point, it takes anywhere between 1-2 hours, so by now we are feeling tired and struggling to catch our breath. Throughout the climb we should try to maintain a slow pace and take fluids constantly to help reduce chances of catching what is known as Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), whose primary symptom is a headache (usually occurring at an altitude above 2500 m) combined with conditions such shortness of breath, nausea or vomiting, or tiredness. Note that a headache can also be a symptom of dehydration. Also, beware of sunburn at a higher altitude as thinner atmosphere provides less protection from the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. It is advisable to apply sunscreen with at least 30 sun protection factor (SPF).

Since we are now above the treeline, we have an unobstructed view of the sky. I should point out that mountains provide a natural and permanent vantage point for observing the upper atmosphere and were used in the past as observing platforms for meteorological observations in the upper air, long before kites and ballons came into being. Nowadays, radiosondes and satellites are routinely used for observing the atmosphere from privileged vantage points in the atmosphere and space, respectively.

Also, here above treeline, we can take a break and look back down on our hiking trail. On a clear day we can see a beautiful country in every direction from south towards the City of Nairobi and to the North towards Nanyuki Town. The landscape stretches westwards towards the Aberdare Mountains, which form part of the eastern arm of the Great Rift Valley. The altitude variation gives rise to a fairly well defined vegetation belts as shown in Figures 2 (see Part 1), which are associated with different temperatures and rainfall regimes. The agricultural zone extends up to 2800 m in some places on the mountain. The forest zone follows between about 2000 and 3300 m and contains areas of indigenous forest plantations, merging into the bamboo and Rosewood zones with increasing altitude. Looking towards the mountain peak, the moorland zone is found between 3300 and 4000 m and merges into the afro-alpine zone from 4000 4500 m. The so called nival zone (zone of rock and ice) follows, extending up to the top of the summit peaks. The photographs in Figure 2, are arranged from the lowest to highest mountain elevation to highlight the different zones a result of the changing altitude. Students can fly several kites extending to different heights in the atmosphere carrying simple meteorological sensors, such as a thermometer and an anemometer to measure weather parameters and observe changes associated with altitude.

From studies done in the past, rainfall maximums occur on the southeastern side of the mountain (geographers like to call it the windward side) with an annual rainfall > 2500 mm; while the northern side (the leeward side) experiences less rainfall: 800 – 1200 mm. Rainfall amounts also decrease fairly smoothly toward the summit and towards the lowlands. Temperature varies considerably with altitude and diurnal range is considerable. The variation causes wind to blow down the mountain during the night and early morning, and up the mountain from mid-morning to evening. There are more sunshine hours in the northern part than in the south and southeastern parts, which are obviously more cloudy.

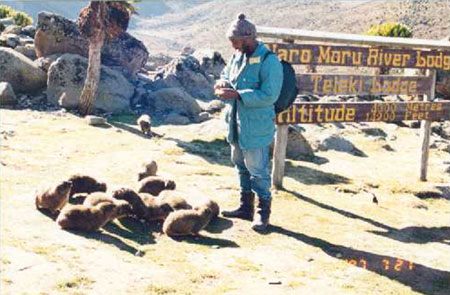

Next, we continue our long trek uphill on Teleki Valley and arrive at Mackinders Camp at 4200 m. Note that from the Met Station to Mackinders Camp, it is a distant of about 10 km and an ascent of 1935 m. It is quite a long stretch to walk and can take anywhere between 5 and 15 hours, depending on prevailing weather conditions. Wet weather is not good for climbing this mountain. This is not our destination, but it offers a good place to rest and enjoy views of the magical twin peaks of Mt Kenya (see Part 1, Figure 2f). Batian Peak is on the left and Nelion on the right and there is a small glacier at the base, where the snow comes down the Couloir (not visible in the picture). This is more than a camp; it is a large stone hut with multiple bunk rooms and set up to cater to a large trekking groups that come through here. Small mammals known as the mountain hyrax abound in this area and can be seen lying happily on the rocks enjoying the sunshine and others scuttering around (see Figure 4).

Our station is a little further towards the summit at 4220 m, about 30 minutes from Mackinders camp. We will spend a night at Mackinders and continue to the sampling station in Part 3.

Fig.4. This is me in the picture with the small mammals, the rock hyrax. These mammals are rat-like in appearance, but with a stumpy tail, and about the size of a domestic cat. Despite their size and appearance, their closest living relative in the animal kingdom is the Elephant. Although not visible, hyraxes have surprisingly large tusks.

The the rock hyrax looks lovely.

i wish one day i can join to Research Expedition.

You mention the different zones that extend up the mountain, such as the agricultural zone, forest zone, moorland zone and afro-alpine zones. Has there been any change in these zones over the last 10 to 20 years? How much of that is related to climate change?

Research Expeditions were dream of mine when i was younger.

It looks like something you will never forget.